You may have come across a porcelain hair receiver at an estate sale or while thrifting and wondered what it was. I have seen them grouped with tea sets, separated, and once, sold with an egg cup as a warming cover. The quotidian items associated with grooming and presentation are some of the most personal connections to the lives of those who lived before us. A brush, a powder jar, or the sharp patterns cut into crystal jars with silver lids were the mis en scene for women’s morning routines. These items were displayed proudly and reflected the personality and aesthetic preferences of those who owned and used them. The personal nature of these items meant that the gift could be freighted with meaning and hint at intimacy or love.

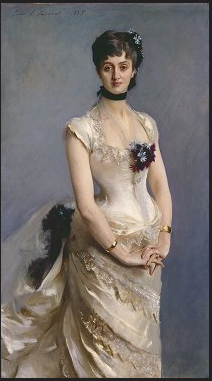

Hair receivers are small porcelain jars with an open hole in the top. At the end of the nineteenth-century, they were sometimes given with a matching powder jar. This example is typical of the era, circa 1890, and is hand painted with feminine florals. In the nineteenth century, a woman’s long hair was considered erotic. The Art Nouveau whorls and curls of Alphonse Mucha’s women, interspersed with the smoke of the Job cigarettes he was illustrating, have become decoupled from the advertising he was commissioned for and represent an idealized femininity and bohemianism exemplified by a woman’s long hair displayed publicly. For those who towed a more Puritan middle class line, however, women’s hair could not be displayed hanging down as a sensual curtain, but was instead to be pinned, curled, braided, bowed, and tucked back in various fashionable styles, and always under a hat when out of the house.

It was only in her bedroom that a woman could unpin her hair and leave it long. Brushing her hair was a morning and evening ritual done at her toilette table, and the accumulated hair in the hairbrush was put into the hair receiver. Why would she not simply have binned it or burned it? She saved her dead locks to make ‘rats’ upon which to build elaborate up-dos. A woman with flowing, abundant hair was not only seen as sensual, but also healthy and robust, and the abundance of hair was also interpreted by some to reflect passion. Victorian magazines abound with hair styling devices; false curls, ringlets, hair pins, curlers, curling tongs, and a myriad of diverse accoutrements. Hair was womanhood, in all it’s tamed and untamed glory. Men wrote about the erotic ‘hair curtain’ that hung around a woman’s naked body in the privacy of her bed chamber.

By making her hair ‘rats’ with her own hair, a woman could improve the fullness of her locks and answer honestly when a suitor asked “Is that all your own hair?”